Inclusivity - Why a slight change can go a long way

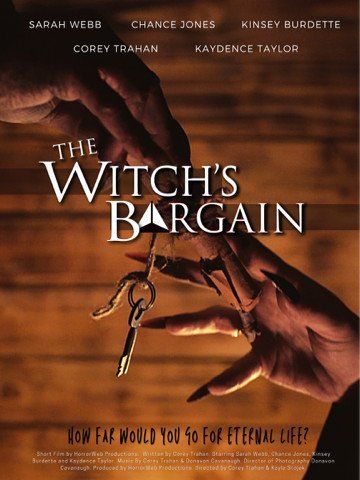

Inclusivity should be second nature, unfortunately, we are not yet at that stage. This year we have a film showing at the Romford Horror Festival that has inclusive language, The Witch's Bargain. Although it is only a couple of lines, it means the world to those who are often forgotten about in the realm of film. Gender and LGBT representation may not mean a lot to many film directors, but it has more of an impact than one may realise.

We yearn for a wholesome LGBT+ narrative that is not clouded with trauma and abuse. Watching coming out story after coming out story that ends in violence, getting thrown out of the house and lost love just solidifies that our lives are based on horrific events. Specifically, bisexuality is a term that is often not said in film or TV. Female characters such as Lilly from How I Met Your Mother (2005) is happily married, yet she daydreams of kissing Robin, this is then passed off as a joke. Dodgeball (2004) uses the term bisexual, then immediately perpetuates the stereotype of bi women being in open relationships, demeaning same-sex couples. Orange is The New Black (2013) refused to use the term Bisexual until very late in the show adding to Bi erasure, despite the main lead sleeping with people of different genders. More horrifying is the fact that the term ex-lesbian was used to describe a bi woman in a relationship with a man. This lack of representation makes it harder for Bi people to come out, as their identity is seen as a phase, an experiment or worst of all, a fetish.

This isn’t to say that every film should have a queer main role and use all the current buzzwords found online but to simply acknowledge that queer people can have boring mundane lives, like everybody else. This can be done by hiring more LBGT+ staff, writers, directors, producers, who will all have a different lifestyle, and can contribute this to the film. Broad City (2015) really raised the bar with their positive representation of bisexual and gay characters. A Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019) also has wonderful representation as it doesn’t sexualise the lesbian characters, something that often contributes to the male gaze.

Considering avoiding Queer coded villains helps avoid further embedding the narrative that Queer people are inherently evil. An example of a Queer coded villain is Ursula from The Little Mermaid (1989) who has stereotypical gay attributes such as the butch haircut. Although they are never officially described as Queer, the mannerisms and looks indicate there is a clear underlying message.

They say ‘write what you know’, and Queer writers will always give a truer representation, but that doesn’t mean you can’t include an gay character, just don’t tell their story. I could go on and on about the representation of the LBGT+ community in many films and TV shows, but that is for another time. I simply want to emphasise that we exist, and maybe consider if you have accidentally made all your characters straight, a slight change can go a long way.